Belonging in fractured Britain: an argument for ritual

If we're going to pull together as a country, we need to get back to our rituals.

Across Britain, there’s a quiet, growing ache. A longing for something we can’t quite name, but feel in our bones. It’s not just the yearning for a more stable political and economic reality, though that does play a part. This ache goes deeper. The ache is a symptom of the disconnection from our collective identity. We are unsure of who we are, where we have been, and what we’re becoming.

It’s cultural rootlessness. A frayed thread running through our collective psyche. You can hear it in the national debates about “British values.” You can see it in the private searches for meaning, purpose, and belonging. You can feel it in the restlessness of the yuppie flying to the Amazon to smoke toad venom, or the lads circling a retail park on Friday night. People are searching for something.

For meaning. For transcendence. For a sense of being a part of something real, bigger than themselves. And whether they know it or not, what they’re searching for is ritual.

Ritual is how we remember what it means to belong – to place, to people, to purpose. It’s how we mark time, make sense of change, and root ourselves in something sacred. But in a country that’s forgotten itself, where do we begin to belong again?

A Nation Disconnected From Itself

Modern Britain doesn’t know who it is anymore. The old myth of the British nation – empire, order – has crumbled. What’s left is a patchwork of cultures, experiences, and histories. Rich, but disjointed. If there’s been no collective reckoning of how we’ve got to where we are, there can be no honest reimagining of what comes next. So we become stuck in a culturally paralysed relationship between nostalgia and disassociation.

This crisis plays out everywhere. You can see it in our politics, our media, our institutions. It’s not just about political parties, but about ideas of nationhood. On one side, we see an aggressive rigidity: a desperate grip on an imagined past of purity and control, blind to the richness multiculturalism has brought. This is the path toward a fascistic society, a path that tries to bleach the past of complexity, forgetting that “Britishness” was never singular. It lacks the recognition that the very ‘British’ culture held onto is deeply entangled with the rest of the world.

The British Empire didn’t just dominate; it interwove. It reimagined Britain as the centre of a global web, the “motherland” in the minds of millions across its colonies. That fantasy echoes still. My Nigerian-born grandmother speaks of Britain with reverence, as if its image was stitched into her sense of possibility. That image didn’t just emerge; it was designed, exported, consumed.

To pretend British identity was ever isolated is to deny history. The truth is: Britain has always been hybrid (Anglo-Saxon is funnily enough the only millennia-old nationality with a hyphen!). The cultures it absorbed, exploited, and exchanged with, shaped it as much as its own internal traditions. This isn’t to romanticise the violent and fraught legacies of colonialism. Rather, it is a call for understanding the complexity honestly. Naming that legacy, however uncomfortable, is the first step toward a sense of belonging that can be all-encompassing of our past. Meanwhile, the progressive side often avoids the question altogether. In trying to create an inclusive present, they shy away from the culture of this land that existed before the demographic shift, and this forgets the power of the stories, customs and rituals that once rooted people to land, season, and spirit. Without those roots, “diversity” becomes fragmented. Coexistence without cohesion. A cacophony of beautiful voices, but without the shared rhythm of a chorus.

Neither extreme works. What we need is a balance between unity and diversity, between rootedness and openness. One that welcomes multiplicity, but also seeks continuity. One that doesn’t fear the past, nor ignore it, but gathers it up and makes compost of it to grow something new.

And to walk that path, we’ll need to do something very un-British. We’ll need to get spiritual.

The Return of Ritual

When the stories that once tethered us unravel, ritual can weave new threads.

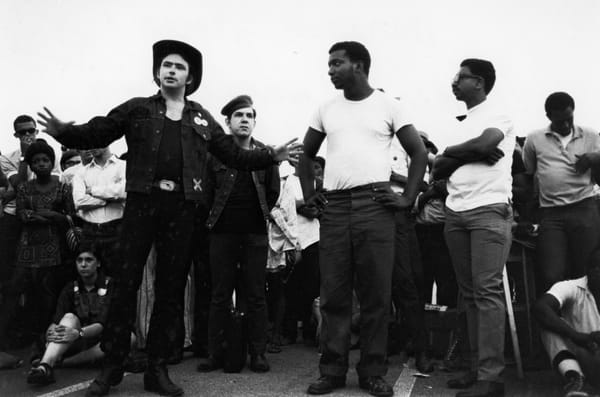

Ritual isn’t just incense and chanting. It’s the embodied language of belonging. It’s movement, memory, and meaning braided together. It’s what lets us feel ourselves not just as individuals, but as a society; with each other, with the land, with something bigger than us all. Not necessarily in the religious sense, but in the deeper, older sense of being connected to something larger than oneself. People are still practicing spirituality and rituals all the time, they just don’t call them that anymore. Pilgrimages to football stadiums.

Drumming at Notting Hill Carnival. Nights out where you lose yourself in music, sweat and movement, where strangers become kin on the dance floor.

Artist Jeremy Deller's history of rave charts some of the cultural changes of how we belong.

These are not just leisure activities, they are rites of communion. Psychologist Martha Newson’s research into identity fusion, that visceral sense of being bonded so closely to a group that you’d act self-sacrificially for it, shows that shared, embodied rituals are among the strongest tools we have for creating deep belonging. Whether it’s religious ceremonies, football chants, or illegal raves, these acts do more than connect us.

Newson identifies four recurring ingredients (the 4Ds) that make rituals powerful enough to rewire our sense of self and belonging: Dance, Drums, Drugs, and Deprivation. All of them shift us out of the ordinary and into a heightened state of connection with each other, with the moment, with something more and dare I say it something spiritual. They offer what so many are starved of: connection, presence, transformation. They’re deeply felt, embodied experiences of belonging. The problem is that many of these rituals are disconnected from any wider story. They’re just floating experiences. Still meaningful. Still powerful. But unanchored. Not embedded in intentionality to the creation of something that can hold us together in the long term.

And so the longing persists. Yet, across the UK, something ancient is stirring. A resurgence of folk culture and ancient rituals playing a role. Usually dismissed as quaint or archaic, seasonal festivals, land-based customs, and rituals are being reimagined. Not as heritage for tourists but as living practices of finding belonging.

All female Morris dancing collective Boss Morris. Angeline Morrison, a singer re-storying the historic black presence in Britain dating back to Roman times through song. Stone Club. Weird Walk. The Folk Dance Remixed, where the maypole meets hip-hop dance anthems. These aren’t nostalgic reenactments. They’re Revivals. Reclamations of the old, but speak to the now.

They offer something the modern world has stripped away: seasonality, place-based time, communal care. Folk traditions and rituals have always been grounded in what’s universally human: the sun, the moon, the turning of the seasons. They’re ancient, yet adaptable.

I felt this viscerally in 2022, dancing on the estate of Richard Benyon with the Right to Roam campaign. It was a protest, but we called it the Dance of the Commons.

As we danced, laughed and sang, re-enacting customs rooted in land once shared, I was struck by how familiar it felt. Not in a British way, in an Igbo way. It echoed the Mmanwu masquerades of my ancestry. From that moment, I began to see the parallels everywhere: from Whittlesea Straw Bear to the Mkpamkpanku, both donning garments made of hay and parading around.

From Iwa Ji (New Yam Festival) to Lughnasadh, all are rituals of harvest honouring land and life’s sacred cycle.

These shared rituals deepened my connection to both my ancestral culture and to Britain, my home. Creating a sense of belonging that showed me that being Nigerian and British doesn’t have to be an either-or. It can be an and. It told me I belonged, not in spite of my hybridity, but because of it. These traditions and rituals allow for us to see our collective humanity, holding similarity and difference.

This is the revolution of folk ritual: it can expand who gets to belong.

The challenge is to reimagine folk culture: not as something closed and backward-looking, but as something living. Something that can be rooted in heritage while remaining open to evolution. Because the makeup of the “folk” of this land has changed and is still changing.

The real task now is to create a culture that reflects that shift. A culture that honours the traditions, customs and ritual of the old associated with the land; that sees the similarities in the ancestral cultures of the people who have migrated here too; and dares to reweave a folk culture to meet the folk now. Because if we can do that, then maybe we can begin to build a new kind of belonging. One that holds space for both history and hope.